![]()

You’ve probably heard of the Silk Road, the ancient trade route that once ran between China and the West during the days of the Roman Empire. It’s how oriental silk first made it to Europe. It’s also the reason China is no stranger to carrots.

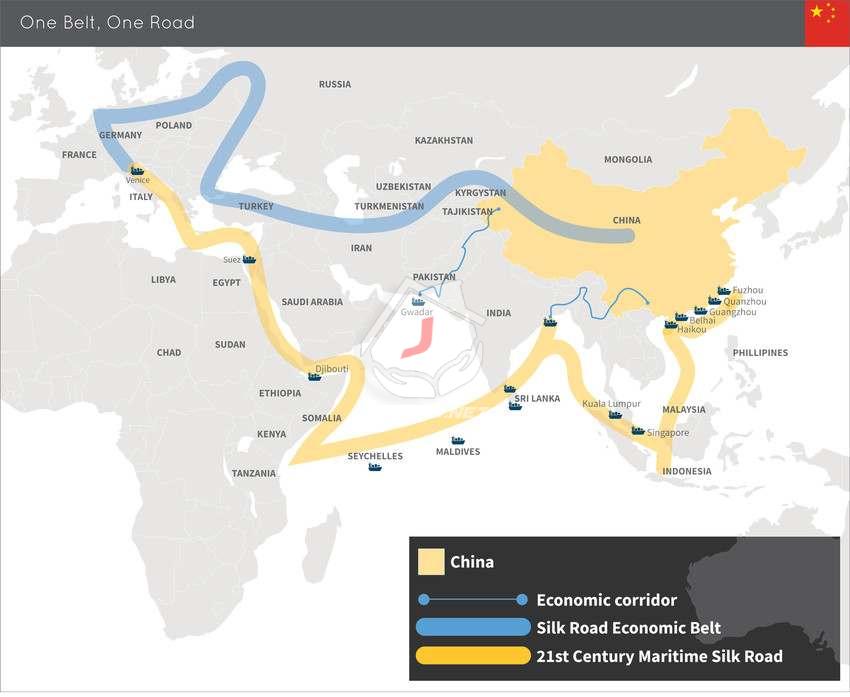

And now it’s being resurrected. Announced in 2013 by President Xi Jinping, a brand new double trade corridor is set to reopen channels between China and its neighbours in the west: most notably Central Asia, the Middle East and Europe.

According to the Belt and Road Action Plan released in 2015, the initiative will encompass land routes (the “Belt”) and maritime routes (the “Road”) with the goal of improving trade relationships in the region primarily through infrastructure investments.

The aim of the $900 billion scheme, as China explained recently, is to kindle a “new era of globalization”, a golden age of commerce that will benefit all. Beijing says it will ultimately lend as much as $8 trillion for infrastructure in 68 countries. That adds up to as much as 65% of the global population and a third of global GDP, according to the global consultancy McKinsey.

But reviews from the rest of the world have been mixed, with several countries expressing suspicion about China’s true geopolitical intentions, even while others attended a summit in Beijing earlier this month to praise the scale and scope of the project.

The project has proved vast, expensive and controversial. Four years after it was first unveiled, the question remains:

Why is China doing it?

One strong incentive is that Trans-Eurasian trade infrastructure could bolster poorer countries to the south of China, as well as boost global trade. Domestic regions are also expected to benefit – especially the less-developed border regions in the west of the country, such as Xinjiang.

The economic benefits, both domestically and abroad, are many, but perhaps the most obvious is that trading with new markets could go a long way towards keeping China’s national economy buoyant.

Among domestic markets set to gain from future trade are Chinese companies – such as those in transport and telecoms – which now look poised to grow into global brands.

Chinese manufacturing also stands to gain. The country’s vast industrial overcapacity – mainly in the creation of steel and heavy equipment – could find lucrative outlets along the New Silk Road, and this could allow Chinese manufacturing to swing towards higher-end industrial goods.

Have you read?

A new global superpower

Some Western diplomats have been wary in their response to the proposed trade corridor, seeing it as a land grab designed to promote China’s influence globally, but there’s little evidence to suggest the route will benefit China alone.

The scheme is essentially a “domestic policy with geostrategic consequences, rather than a foreign policy,” Charles Parton, a former EU diplomat in China, told the Financial Times.

There’s no doubt that China is growing into a geopolitical heavyweight, stepping into the breach left by the United States on matters of free trade and climate change.

“As some Western countries move backwards by erecting ‘walls’, China is contriving to build bridges, both literal and metaphorical,” ran a recent commentary by Xinhua, a Chinese state-run media agency.

Bridges are key to China’s strategy, says Kevin Liu, Chairman of Asia, Partners Group.

He explains: “The superpower status the US has achieved is to a great extent grounded on the security blanket it offered to its allies. Geopolitically, China decided a long time ago that security was too expensive an offer to make. Instead, this new superpower may offer connectivity.”

If combined with enhanced global connectivity, China’s enormous gravity could become an even more meaningful engine for the global economy,” Liu adds.

Which countries stand to gain?

Sixty-two countries could see investments of up to US$500 billion over the next five years, according to Credit Suisse, with most of that channelled to India, Russia, Indonesia, Iran, Egypt, the Philippines and Pakistan.

Chinese companies are already behind several energy projects, including oil and gas pipelines between China and Russia, Kazakhstan and Myanmar. Roads and infrastructure projects are also underway in Ethiopia, Kenya, Laos and Thailand.

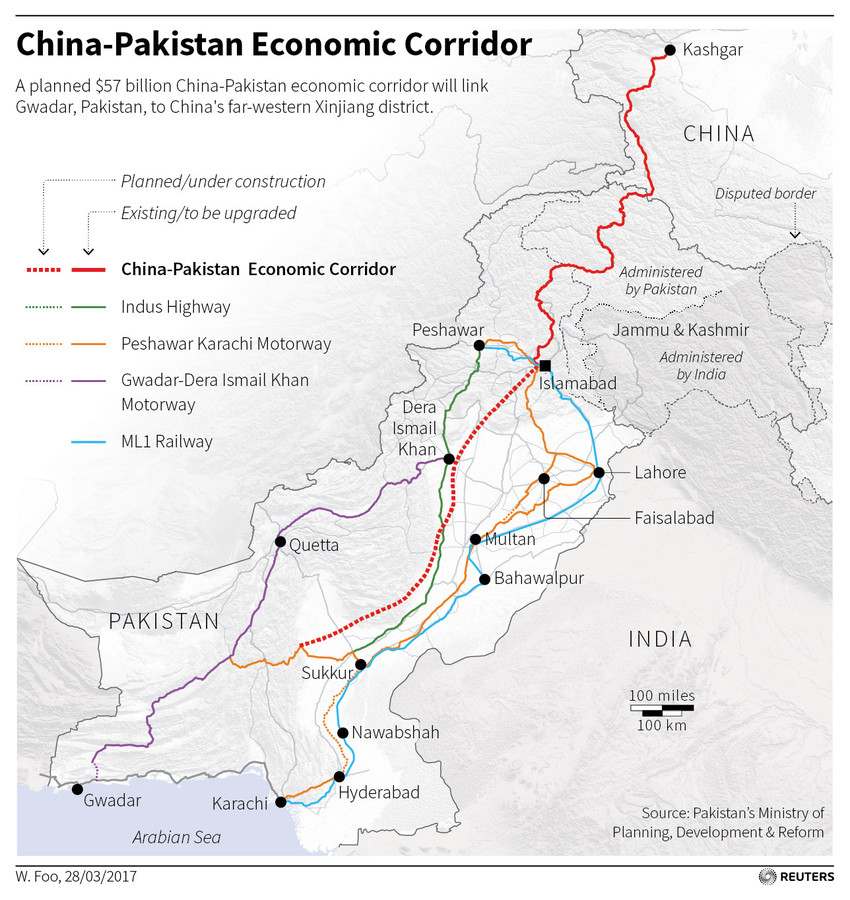

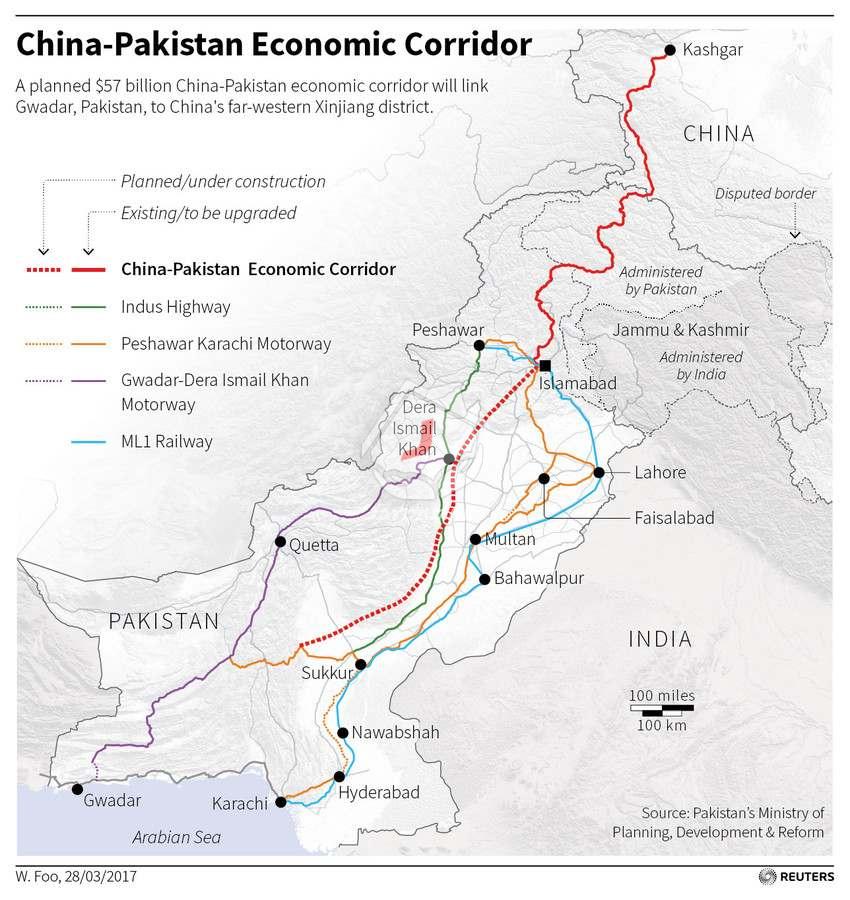

Pakistan is one of the New Silk Road’s foremost supporters. Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif said the trade route marked the “dawn of a truly new era of synergetic intercontinental cooperation”. Unsurprising praise perhaps from a country that stands at one end of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, where it is poised to benefit from $46 billion in new roads, bridges, wind farms and other China-backed infrastructure projects.

Support has come from further afield as well, with Chile’s president, Michelle Bachelet, predicting the route would “pave the way for a more inclusive, equal, just, prosperous and peaceful society with development for all”.

Who’s against it?

Perhaps the route’s most vocal critic so far has been India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Vehemently opposed to the $46 billion China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, which runs through a part of Kashmir claimed by India, he has called the route a “colonial enterprise” that threatens to strew “debt and broken communities in its wake”. He even boycotted the recent One Belt One Road summit in Beijing.

Modi wasn’t the only leader notably absent from the gathering. No officials from Japan, South Korea or North Korea made an appearance, and of the Group of Seven (G7) industrialized nations, the only representative to attend was Italian Prime Minister Paolo Gentiloni.

“While countries welcome Beijing’s generosity, they are simultaneously wary of its largesse. China’s growing influence is a concern for nations whose political interests do not always align with Beijing’s,” explains Paul Haenle, director of the Carnegie-Tsinghua Centre for Global Policy.

While China’s growing influence is a concern for nations whose political interests aren’t aligned with Beijing’s, Chinese spokespeople have repeatedly denied charges of a play for global dominance.

The New Silk Road is “not and will never be neocolonialism by stealth”, China announced recently in state media.

Who’ll foot the bill?

The One Belt One Road project already has $1 trillion of projects underway, including major infrastructure works in Africa and Central Asia.

Ahead of the Beijing summit earlier this month, the China Development Bank had set aside almost $900 billion alone for more than 900 projects. China’s Big Four state-owned banks extended an estimated $90 billion in loans to the economies related to the initiative last year alone.

The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, which was launched in January 2016, has authorized capital of $100 billion. $20 billion will be paid-in capital from 80 shareholders, of which China is the largest with a 28% share.

Despite this largesse, though, the AIIB has provided less than $2 billion in funding over the past year. The bank’s president, Jin Liquin, told the World Economic Forum summit in China last year: “We will support the One Belt, One Road project. But before we spend shareholders’ money, which is really the taxpayers’ money, we have three requirements.”

What were these? The new trade route would have to promote growth, be socially acceptable and abide by environmental laws, Jin said. How well the project fares against these three criteria has yet to be seen.

License and Republishing Written by

Anna Bruce-Lockhart, Editorial Lead, Head of Social Video, World Economic Forum

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.